Industry Practice vs Design Reality in Sewage Treatment Plants

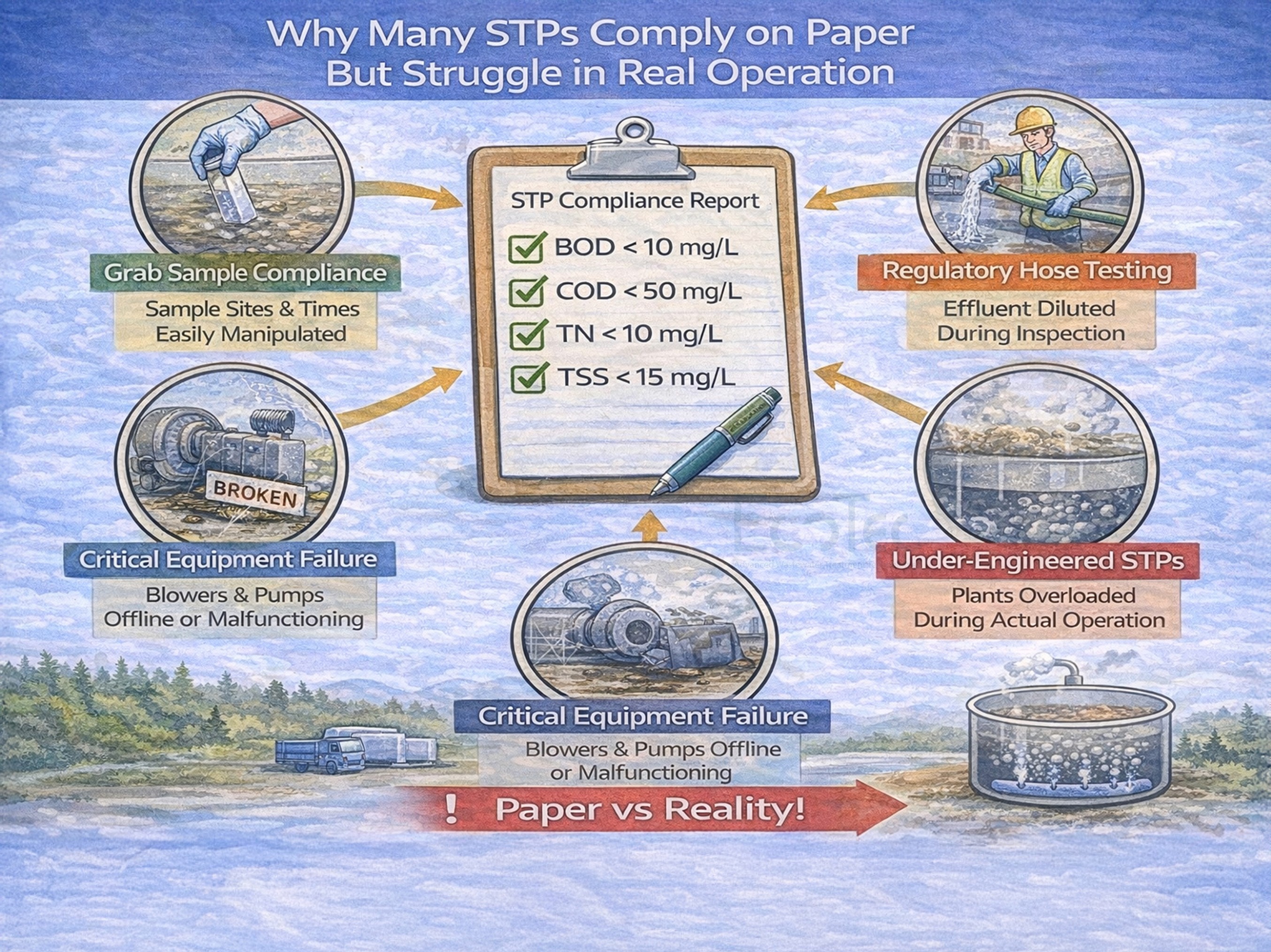

Why many STPs comply on paper but struggle in real operation

When Standard Practice Delivers Standard Problems

Across India, most sewage treatment plants (STPs) are designed, built, and evaluated using well-established industry practices. These practices are aligned with discharge norms issued by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) and are widely accepted by consultants, vendors, and approving authorities.

Yet, despite following accepted norms, many STPs:

Show inconsistent COD and nitrogen removal

Consume more energy than expected

Require frequent operational correction

Degrade in performance over time

This highlights a growing gap between what is commonly practiced and what biological systems actually need to perform reliably.

What Industry Practice Typically Looks Like

In most projects, STP design follows a familiar pattern:

Fixed inlet assumptions based on “typical domestic sewage”

BOD used as the primary organic design parameter

COD treated as a secondary or reporting parameter

Aeration sized conservatively to ensure compliance

Performance judged mainly on outlet test results

This approach offers:

Simplicity

Ease of standardisation

Predictability during approval and commissioning

However, it also embeds several biological blind spots.

Design Reality: Biology Does Not Follow Assumptions

Biological treatment systems do not respond to:

Average values

Single-number parameters

Fixed time cycles

Instead, biology responds to:

COD fraction availability

Reaction timing

Stability of loading conditions

When design is driven primarily by BOD and averages, it assumes that:

All organic matter behaves similarly

Oxygen demand is uniform over time

Biology will adapt automatically

In reality, these assumptions often break down.

Gap 1: Inlet Assumptions vs Actual Wastewater Behaviour

Industry practice relies heavily on standard inlet values.

In reality:

Domestic sewage varies significantly by location and usage

Mixed-use developments introduce non-domestic COD fractions

Seasonal and diurnal variations alter reaction behaviour

When actual wastewater deviates from assumed characteristics:

Aeration strategies become misaligned

COD removal becomes unpredictable

Nutrient performance suffers

The plant still “meets design,” but struggles to perform.

Gap 2: What Is Committed vs What Governs Performance

Most STP suppliers commit to:

BOD

COD

TSS

pH

These are output parameters and are necessary for compliance.

However, they do not describe:

COD fraction behaviour

Reaction timing

Carbon availability for denitrification

Energy Efficieny

As a result:

Multiple plants meet identical commitments

Actual performance and operating cost vary widely

The difference lies not in commitments, but in design logic.

Gap 3: Aeration as Insurance, Not as a Process Tool

Industry practice often treats aeration as:

A safety margin

A means to absorb uncertainty

A way to “guarantee” compliance

This leads to:

Longer aeration durations

Higher blower capacities

Increased energy consumption

While this may help meet outlet numbers, it:

Masks biological inefficiencies

Does not improve reaction timing

Does not address COD fraction limitations

Aeration becomes an insurance policy—not a process enabler.

Gap 4: Nutrient Removal Treated as an Add-On

With evolving regulatory expectations, nutrient removal is increasingly required.

Industry response often involves:

Adding anoxic zones

Increasing aeration control complexity

Relying on operational adjustments

However, without understanding carbon availability and timing, these measures:

Deliver inconsistent results

Depend heavily on operator intervention

Increase system sensitivity

Nutrient removal cannot be reliably “added” to a BOD-designed system.

It must be designed into the biology from the start.

Why These Gaps Persist

These gaps are not due to negligence. They persist because:

Standardisation simplifies procurement

Conservative design reduces approval risk

BOD-based thinking is deeply ingrained

Biological behaviour is harder to explain than equipment capacity

However, as regulatory and performance expectations rise, these compromises become more visible.

The Cost of the Gap

When industry practice diverges from biological reality, the cost appears as:

Higher operating expenses

Lower resilience to load variation

Shorter intervals between interventions

Difficulty sustaining long-term compliance

These costs are rarely captured at design stage—but are paid throughout the plant’s life.

How This Leads to the Next Question

If:

Most vendors commit to similar numbers, and

Most plants are built using similar assumptions,

then the real question becomes:

What kind of design approach aligns industry practice with biological reality?

This leads directly to the final article in this series.

What to Read Next

Conclusion:

Industry practice has enabled rapid deployment of STPs and broad regulatory compliance.

However, long-term stability, energy efficiency, and nutrient control require a deeper alignment with biology.

Bridging the gap between practice and reality does not mean abandoning standards—it means evolving design thinking to reflect how sewage actually behaves.